Geneviève Wiels / Thomas Mouzard

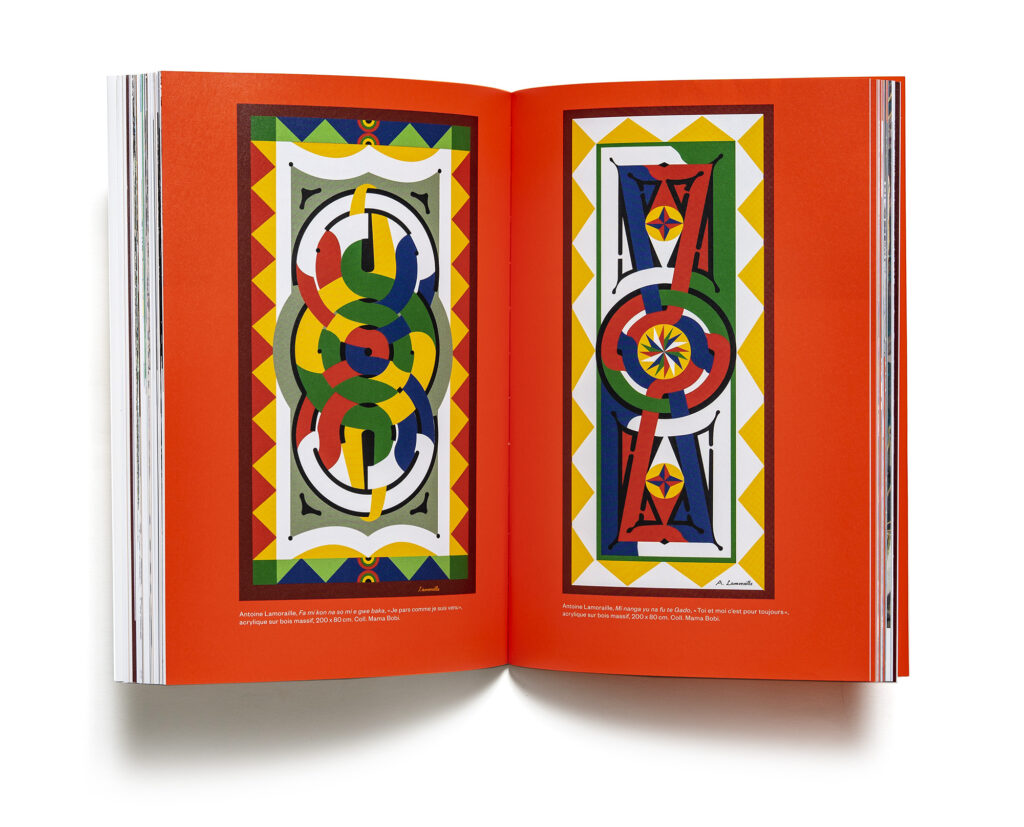

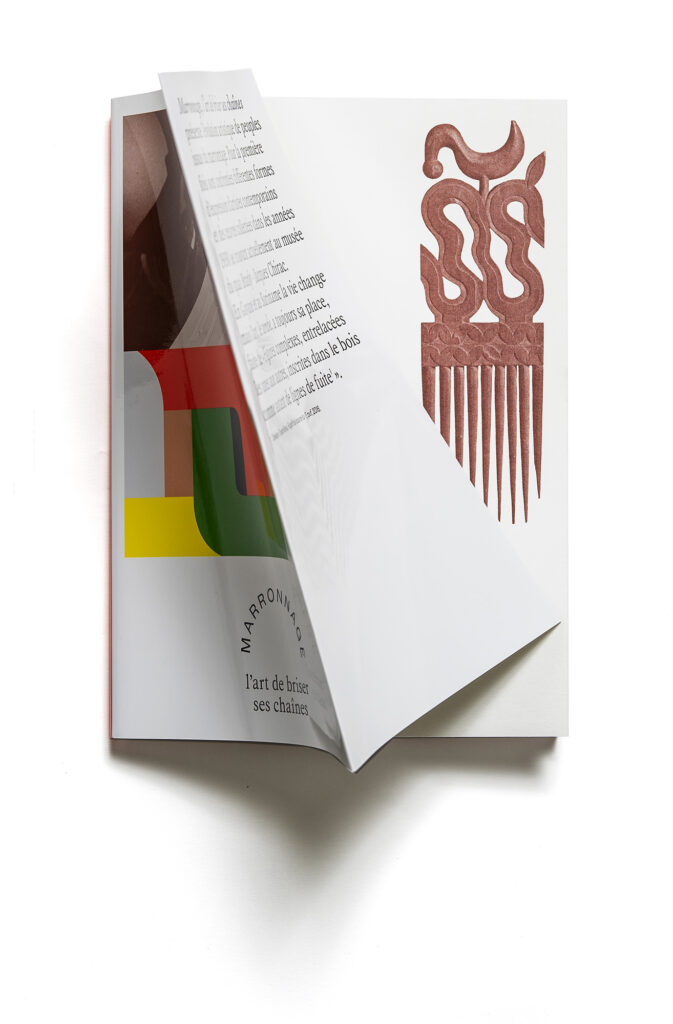

In all the countries where slave ships forcibly transported them, enslaved people fled. They are called “maroon” slaves, and it is said that they went into maroonage. In Dutch Guiana (Suriname), slaves fled in large numbers, protected by the immense Amazon rainforest nearby, where they formed communities. The art of breaking one’s chains is the little-known story of marronage. These Maroon societies first had to defend their freedom, build on what remained of their African cultures, then develop and, once peace returned (around 1860), express their sense of beauty through art: the moy. Under the artist’s fingers, everyday objects became works of art made for oneself or given to others, especially to one’s beloved. Marronnage, the art of breaking one’s chains, is also tembe, the art of the Maroons: sculpture, engraving, embroidery, and painting. Alongside sculptures and objects from the last century (most of which come from the Quai-Branly Museum), the works of contemporary artists are presented, highlighting for the first time the artistic continuity of Maroon art. Readers will discover the works of pioneers of tembe on canvas such as Antoine Lamoraille and Antoine Dinguiou, as well as the paintings and sculptures of their younger counterparts Carlos Adaoudé and Francky Amete. Original creations by internationally renowned painters such as John Li A Fo and Marcel Pinas are also featured.

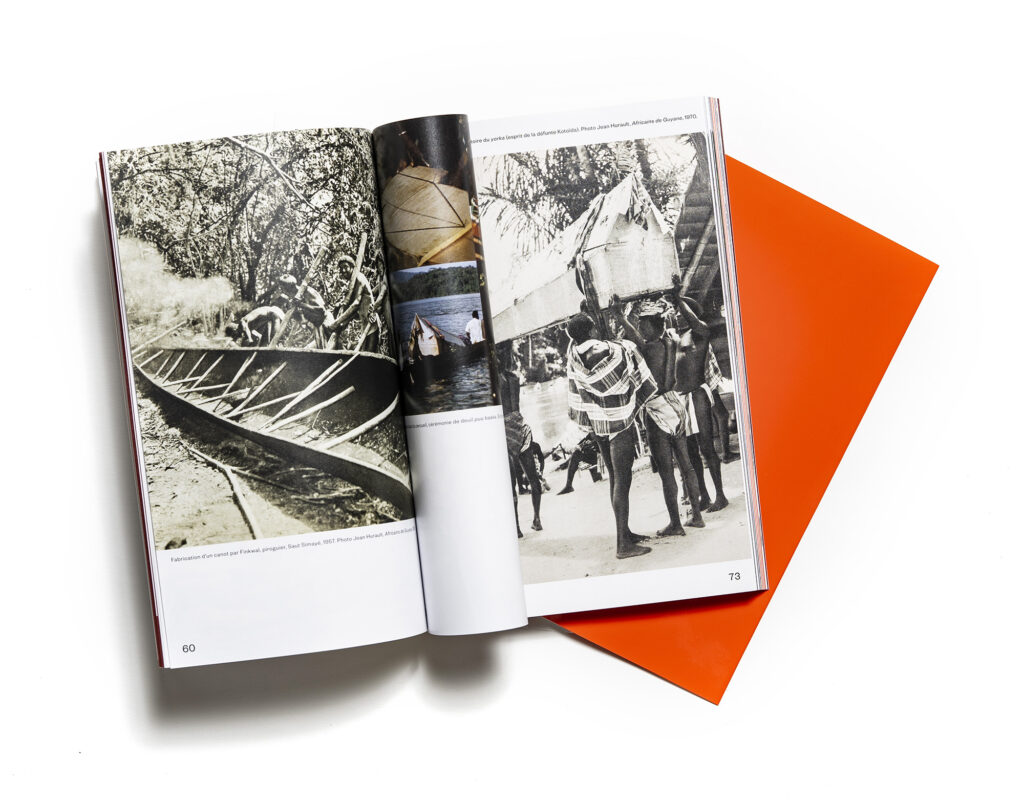

Scientists from the last century also brought back photographs, whose artistic value is clear to us beyond their documentary value. Showing the same collective subject matter several generations apart, the works of contemporary photographers such as Gerno Odang, Ramon Ngwete, and Nicola Lo Calzo enter into dialogue with those of ethnologists Jean-Marcel Hurault and Pierre Verger. To understand these peoples, who rose up against the fate that had been reserved for them, the floor will be given to witnesses, both those from the time of slavery and those of today.